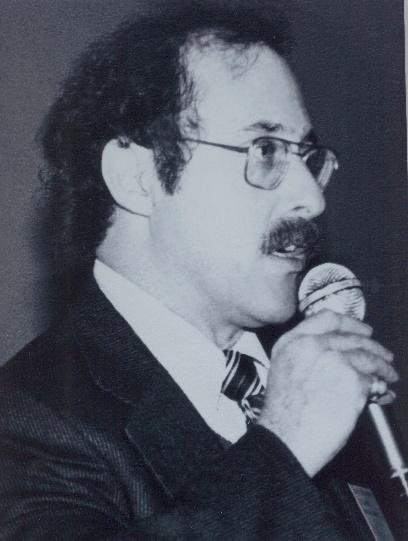

The Wallach Revolution

The Citizens Committee for Better Medicine is proud to present “The Wallach Revolution – (An Unauthorized Biography of a Medical Genius)”. The book is now available and chronicles the challenges, successes, and unique perspective of Dr. Joel D Wallach, a true pioneer in the field of science-based, clinically verified medical nutrition. (No portion of the content on this site may be exhibited, used or reproduced by any means without express written permission of the publisher.) Click HERE to get your copy of this brand new book!